In the wake of white supremacist Dylan Roof's murder of nine parishioners in a historic South Carolina Church, there have been a lot of calls recently to abolish any display or sale of Confederate flags. There is no question that, for many people, the Confederate flag is a symbol of intolerance, slavery, and hatred, which has led to call for the Confederate flag to be abolished from our popular culture.

Let me state up front that I unequivocally condemn Roof's actions. He's a murderer who deserves to have the full weight of the law come down on him.

That said, here are my thoughts on the Confederate flag.

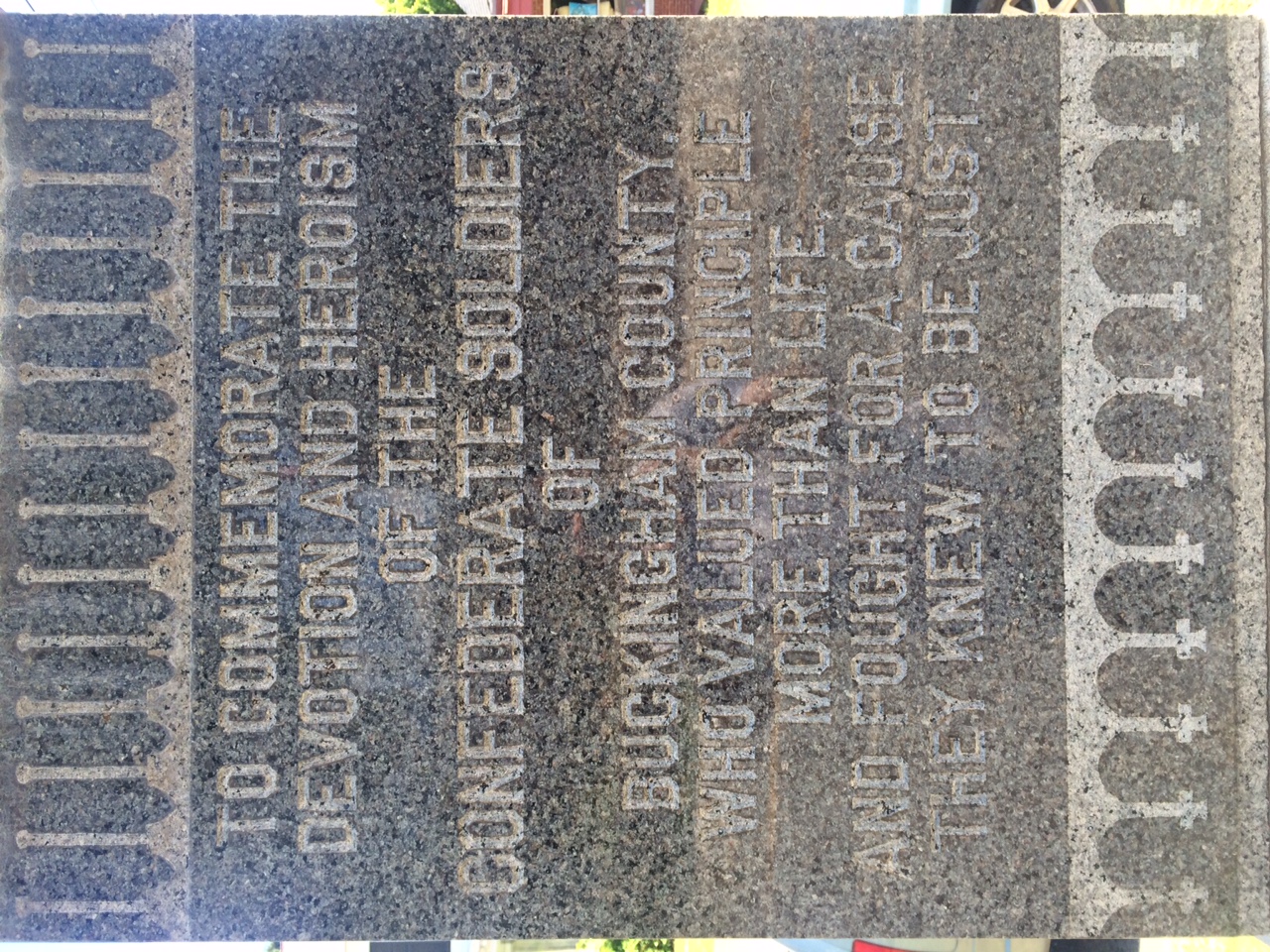

Seventy miles west of Richmond, Virginia on US Rt. 60 sits Buckingham Courthouse, an edifice designed by Thomas Jefferson. Across the street from that building sits a Confederate war memorial, flanked by a pair of Napoleon guns (still pointing north, I must add).

As a young boy growing up, I saw that monument almost daily, as I had to pass by it on the way to church or school; but I never thought much of it. Finally, one day in my mid-teens, I wandered over to it and read the inscription. It reads, in all caps:

"To commemorate the

devotion and heroism

of the

Confederate Soldiers

of

Buckingham Country

who valued principle

more than life

and fought for a cause

they knew to be just."

That was perplexing. "...a cause they knew to be just"? How, in Heaven's name, I wondered, could anyone think that defending slavery was a just cause? It boggled the mind. It wasn't until I became a military analyst years later that I finally understood and learned that history is always much more complicated than it appears in hindsight.

Most modern Americans would probably be surprised to learn that if you asked a Northerner in 1861 why he was going to war against the South, his answer would not have been any variation of "to eliminate slavery." His answer would have been "to preserve the Union."

For example, in August 1862, newspaper editor Horace Greeley published an open letter to President Abraham Lincoln in the New York Tribune, in which he questioned Lincoln's commitment (in scolding terms) to ending slavery and demanded to know just what policy the president was pursuing. Lincoln replied, saying:

"As to the policy I 'seem to be pursuing' as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt. I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be 'the Union as it was.' If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

Lincoln had a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation sitting in his desk drawer when he wrote his reply to Greeley. He'd been sitting on that draft for a month and he would sit on it for almost another month before announcing it. Lincoln thought slavery was a moral evil, but he also viewed eliminating it as a political means to the end of preserving the Union. So he waited to release the Proclamation until the opportune moment when it would hurt the Confederate cause the most--after the Union Army had won a significant battlefield victory (Antietam), when he could act from a position of political strength to inexorably intertwine the abolition of slavery with the war and erase all Confederate hopes of European assistance (the European nations had all abolished slavery and weren't going to help save a slave-holding nation win a war to preserve the institution).

But even after Lincoln released the Proclamation, many Northerners didn't consider abolition to be a paramount goal of the war. George McClellan--an insubordinate general who Lincoln fired twice--ran for president in 1864 as a Democrat. The Democrats that year promoted a platform of ending the war immediately and making peace with the South, which would have let both the Confederate States of America and the institution of slavery survive. McClellan lost to Lincoln but he won 45% of the popular vote.

In November 1864, almost half of all voting Northerners effectively cast a ballot that would have let slavery survive. It was the price they were willing to pay to end the war, one way or the other.

Most modern Americans would probably also be surprised to learn that if you asked a Southerner in 1861 why he was going to war against the North, his answer would not have been "to preserve slavery." His answer would have been "to defend my home" or "to defend my state's rights."

For example, before the Civil War began, Robert E. Lee himself was asked by one of his lieutenants whether he would take up arms against the Union. Lee replied, saying, "I shall never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in the defense of my native state, Virginia, in which case I shall not prove recreant to my duty." Later, when he was offered command of the Union Army by Lincoln adviser Francis P. Blair, Lee replied, "Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves at the South, I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native State?" I've never read a verifiable quote by Lee where he said that he was fighting to preserve the institution of slavery (if anyone knows of one, I'd love to see it).

That slavery was the flashpoint over which the states' rights argument ignited is inarguable; several Southern legislatures made it pretty clear that they considered preserving slavery an existential issue. But it really was the trigger for the larger question--do states have the right to secede from the Union when they believe the US Government isn't being sufficiently deferential to the states? Remember that that was an open question in 1861 and had been since the days of the Founding Fathers. Slavery may have been the burning fuse, but states' rights was the powder keg. The South and the North had grown apart so far economically, politically, culturally, that Southerners really did see themselves as a separate civilization.

Another anecdote to support the point: During the Republican Convention of 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower revealed that he kept a portrait of Robert E. Lee in the Oval Office. Dr. Leon Scott, a New York dentist, wrote to Eisenhower saying, "I do not understand how any American can include Robert E. Lee as a person to be emulated, and why the President of the United States of America should do so is certainly beyond me...Will you please tell me just why you hold him in such high esteem?" Eisenhower's replied with a letter worth reading in its entirety, but I will quote just this section:

Respecting your August 1 inquiry calling attention to my often expressed admiration for General Robert E. Lee, I would say, first, that we need to understand that at the time of the War between the States the issue of secession had remained unresolved for more than 70 years. Men of probity, character, public standing and unquestioned loyalty, both North and South, had disagreed over this issue as a matter of principle from the day our Constitution was adopted.

General Robert E. Lee was, in my estimation, one of the supremely gifted men produced by our Nation. He believed unswervingly in the Constitutional validity of his cause which until 1865 was still an arguable question in America...

Whether states could secede or not was an unresolved issue before 1861. It was not an unjustifiable position to claim that states had a right to secede if they chose. There were no Constitutional provisions, federal laws, or court decisions barring it. And history teaches that when divisive political can’t be resolved using the peaceful means of legislative debate and respected court decisions, they get resolved violently on the battlefield. Hence Clausewitz’s dictum that war is the continuation of politics by other means. One side imposes its will on the other side by force.

As Shelby Foote, the great Civil War historian, put it, "Before the war, it was said 'the United States are.' Grammatically, it was spoken that way and thought of as a collection of independent states. And after the war, it was always 'the United States is,' as we say to day without being self-conscious at all. And that sums up what the war accomplished. It made us an 'is'."

I believe that was the "just cause" to which the Buckingham Courthouse monument refers--not the preservation of slavery, but the defense of one's home from an intrusive federal government, and the preservation of a way of life (which was made possible, it is true, by the institution of slavery, but it was the only way of life they'd known since Jamestown--250 years). At least, that's what the Confederate flag meant to them. (Note: what most people call the "Confederate flag" was actually one of the battle flags of the Army of Northern Virginia; the Confederate States of America had a series of different national flags during its brief existence.)

But in a sense, what they thought is irrelevant. The relevant question is: what does the Confederate flag mean to us now? Without question, for most Americans it's equated with the institution of slavery. It shouldn't be that simplistic, but it is (I blame the education system for doing a lousy job teaching history) and seeing it flown offends large swaths of our countrymen.

So what's the right thing to do? Here's my answer--I'm frustrated that the whole debate is taking place in a climate of ignorance. I would much prefer to see all Americans dive into Civil War history and educate themselves on the nuances of the 19th Century debate about states' rights, slavery, and the other causes behind the war--but that's not going to happen. So I think there should be compromise. Let's take what our society perceives as symbols of hatred and use them to educate people about why past generations wrongly believed their "cause to be just" so we can avoid their mistakes. But let's not confuse education and veneration. Individuals are free to believe what they will, but as a society, we should keep those flags in museums, classrooms, and any other educational, governmental, or even commercial setting where they would be useful for teaching that part of our history.

But let's not fly them from flagpoles.

Addendum: Some have asked me whether I think South Carolina should be allowed to fly the Confederate flag over the state capitol, etc., since it's "part of their heritage." I say no. Setting aside the cultural and emotional questions about whether it represent slavery, etc, it is, if nothing else, the flag of a foreign power (albeit a dead one). Flying the flag of a foreign power is a demonstration of allegiance to that power. South Carolina's sole allegiance should be to the United States of America. It has no more business flying a Confederate flag over its capitol than it would a Chinese or Russian flag.